The law of prayer is the law of belief. What we pray at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is just as important as how we pray it.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Latin at the Abbey!!!1

While the media made much ado about Catherine's wedding dress, Princess Beatrice strange head-gear (for lack of a better word) and the double kiss that the bride and groom shared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, a more important detail caught my attention. At the 8:15 mark of this video exerpt from the Royal Wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, we note a very interesting musical selection. While the official wedding program calls it The Motet, it is, in fact, Ubi Caritas.

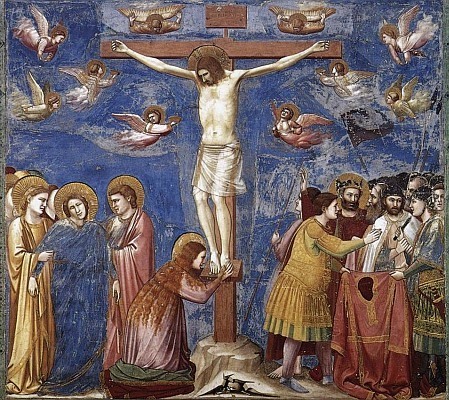

For me, there is great significance in this particular hymn. Ubi Caritas is one of the Church's ancient hymns and is commonly chanted during the Mandatum (Washing of the Feet) during the Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday. The Last Supper seems to me to have wedding banquet connatation to it since it entails an act of love in the deepest sense. Jesus enjoins the remaining 11 Apostles to love one another as He has loved them. Later that night, He shows the depths of His love for not just the Apostolic band, but for all of humanity as He willingly submits Himself to immense suffering, pain and eventually, crucifixion. On the cross, Jesus utters "It is consummated". Thus, the union between God and Man has been completed, much as in the wedding night, the union between husband and wife reaches its ultimate fulfillment.

What strikes me about the particular choice of hymn that William and Catherine made is the fact that it is in Latin. I admit that I do not know much about the Anglican Communion and was rather interested to observe their particular form of liturgy. It was quite interesting to hear Latin at the Abbey. The last time I heard Latin in a televised liturgy from Westminster was when Pope Benedict XVI was there for an ecumenical service. A different setting of Ubi Caritas was used. It was beautiful, nonetheless.

On facebook, I wrote that it was rather ironic to listen to Ubi Caritas in Latin at an Anglican liturgy when in our own Cathedral, we don't even listen to, much less, use, the Church's official languge. When I went to the Anglican-use Mass in Houston, the choir sang in Latin. It was both magnificent and refreshing. It made me think about how we can restore Latin to its rightful place down here in the South Texas hinterland. Perhaps, it would be useful to chant the parts of the Mass in Latin when we have bilingual (English and Spanish) liturgies. After all, Pope Benedict XVI, in Sacramentum Caritatis, strongly recommends this. Rather than sing a mish-mash OCP production-type hybrid of English and Spanish settings of the Mass, we could very well sing the simple chants commissioned by the late Pope Paul VI, Jubilate Deo.

It is certainly worth a try. If Latin in the liturgy is good enough for William and Catherine, certainly, it should be moreso for us, as this venerable language is our birthright and our heritage as Catholics.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Beautiful Marian Easter Hymn

I always enjoy watching the Papal Masses, especially during Easter time. Here is the Sistene Chapel Choir's rendition of the Regina Caeli at the end of the Easter Sunday Papal Mass.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Blessed Anniversary, Pope Benedict XVI

Amdist the Paschal joy that today brings, April 24th marks another cause for celebration. On April 24, 2005, six years ago (right to the day), Pope Benedict XVI was officially installed as the 264th Successor of St. Peter. Throngs of faithful crowded into St. Peter's Square on that bright sunny morning to watch the newly elected Pontiff receive his Pallium and his Fisherman's ring.

Below is the text of the homily that Pope Benedict XVI preached on that historic occasion:

Your Eminences,

My dear Brother Bishops and Priests,

Distinguished Authorities and Members of the Diplomatic Corps,

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

During these days of great intensity, we have chanted the litany of the saints on three different occasions: at the funeral of our Holy Father John Paul II; as the Cardinals entered the Conclave; and again today, when we sang it with the response: Tu illum adiuva – sustain the new Successor of Saint Peter. On each occasion, in a particular way, I found great consolation in listening to this prayerful chant. How alone we all felt after the passing of John Paul II – the Pope who for over twenty-six years had been our shepherd and guide on our journey through life! He crossed the threshold of the next life, entering into the mystery of God. But he did not take this step alone. Those who believe are never alone – neither in life nor in death. At that moment, we could call upon the Saints from every age – his friends, his brothers and sisters in the faith – knowing that they would form a living procession to accompany him into the next world, into the glory of God. We knew that his arrival was awaited. Now we know that he is among his own and is truly at home. We were also consoled as we made our solemn entrance into Conclave, to elect the one whom the Lord had chosen. How would we be able to discern his name? How could 115 Bishops, from every culture and every country, discover the one on whom the Lord wished to confer the mission of binding and loosing? Once again, we knew that we were not alone, we knew that we were surrounded, led and guided by the friends of God. And now, at this moment, weak servant of God that I am, I must assume this enormous task, which truly exceeds all human capacity. How can I do this? How will I be able to do it? All of you, my dear friends, have just invoked the entire host of Saints, represented by some of the great names in the history of God’s dealings with mankind. In this way, I too can say with renewed conviction: I am not alone. I do not have to carry alone what in truth I could never carry alone. All the Saints of God are there to protect me, to sustain me and to carry me. And your prayers, my dear friends, your indulgence, your love, your faith and your hope accompany me. Indeed, the communion of Saints consists not only of the great men and women who went before us and whose names we know. All of us belong to the communion of Saints, we who have been baptized in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, we who draw life from the gift of Christ’s Body and Blood, through which he transforms us and makes us like himself. Yes, the Church is alive – this is the wonderful experience of these days. During those sad days of the Pope’s illness and death, it became wonderfully evident to us that the Church is alive. And the Church is young. She holds within herself the future of the world and therefore shows each of us the way towards the future. The Church is alive and we are seeing it: we are experiencing the joy that the Risen Lord promised his followers. The Church is alive – she is alive because Christ is alive, because he is truly risen. In the suffering that we saw on the Holy Father’s face in those days of Easter, we contemplated the mystery of Christ’s Passion and we touched his wounds. But throughout these days we have also been able, in a profound sense, to touch the Risen One. We have been able to experience the joy that he promised, after a brief period of darkness, as the fruit of his resurrection.

The Church is alive – with these words, I greet with great joy and gratitude all of you gathered here, my venerable brother Cardinals and Bishops, my dear priests, deacons, Church workers, catechists. I greet you, men and women Religious, witnesses of the transfiguring presence of God. I greet you, members of the lay faithful, immersed in the great task of building up the Kingdom of God which spreads throughout the world, in every area of life. With great affection I also greet all those who have been reborn in the sacrament of Baptism but are not yet in full communion with us; and you, my brothers and sisters of the Jewish people, to whom we are joined by a great shared spiritual heritage, one rooted in God’s irrevocable promises. Finally, like a wave gathering force, my thoughts go out to all men and women of today, to believers and non-believers alike.

Dear friends! At this moment there is no need for me to present a programme of governance. I was able to give an indication of what I see as my task in my Message of Wednesday 20 April, and there will be other opportunities to do so. My real programme of governance is not to do my own will, not to pursue my own ideas, but to listen, together with the whole Church, to the word and the will of the Lord, to be guided by Him, so that He himself will lead the Church at this hour of our history. Instead of putting forward a programme, I should simply like to comment on the two liturgical symbols which represent the inauguration of the Petrine Ministry; both these symbols, moreover, reflect clearly what we heard proclaimed in today’s readings.

The first symbol is the Pallium, woven in pure wool, which will be placed on my shoulders. This ancient sign, which the Bishops of Rome have worn since the fourth century, may be considered an image of the yoke of Christ, which the Bishop of this City, the Servant of the Servants of God, takes upon his shoulders. God’s yoke is God’s will, which we accept. And this will does not weigh down on us, oppressing us and taking away our freedom. To know what God wants, to know where the path of life is found – this was Israel’s joy, this was her great privilege. It is also our joy: God’s will does not alienate us, it purifies us – even if this can be painful – and so it leads us to ourselves. In this way, we serve not only him, but the salvation of the whole world, of all history. The symbolism of the Pallium is even more concrete: the lamb’s wool is meant to represent the lost, sick or weak sheep which the shepherd places on his shoulders and carries to the waters of life. For the Fathers of the Church, the parable of the lost sheep, which the shepherd seeks in the desert, was an image of the mystery of Christ and the Church. The human race – every one of us – is the sheep lost in the desert which no longer knows the way. The Son of God will not let this happen; he cannot abandon humanity in so wretched a condition. He leaps to his feet and abandons the glory of heaven, in order to go in search of the sheep and pursue it, all the way to the Cross. He takes it upon his shoulders and carries our humanity; he carries us all – he is the good shepherd who lays down his life for the sheep. What the Pallium indicates first and foremost is that we are all carried by Christ. But at the same time it invites us to carry one another. Hence the Pallium becomes a symbol of the shepherd’s mission, of which the Second Reading and the Gospel speak. The pastor must be inspired by Christ’s holy zeal: for him it is not a matter of indifference that so many people are living in the desert. And there are so many kinds of desert. There is the desert of poverty, the desert of hunger and thirst, the desert of abandonment, of loneliness, of destroyed love. There is the desert of God’s darkness, the emptiness of souls no longer aware of their dignity or the goal of human life. The external deserts in the world are growing, because the internal deserts have become so vast. Therefore the earth’s treasures no longer serve to build God’s garden for all to live in, but they have been made to serve the powers of exploitation and destruction. The Church as a whole and all her Pastors, like Christ, must set out to lead people out of the desert, towards the place of life, towards friendship with the Son of God, towards the One who gives us life, and life in abundance. The symbol of the lamb also has a deeper meaning. In the Ancient Near East, it was customary for kings to style themselves shepherds of their people. This was an image of their power, a cynical image: to them their subjects were like sheep, which the shepherd could dispose of as he wished. When the shepherd of all humanity, the living God, himself became a lamb, he stood on the side of the lambs, with those who are downtrodden and killed. This is how he reveals himself to be the true shepherd: “I am the Good Shepherd . . . I lay down my life for the sheep”, Jesus says of himself (Jn 10:14f). It is not power, but love that redeems us! This is God’s sign: he himself is love. How often we wish that God would make show himself stronger, that he would strike decisively, defeating evil and creating a better world. All ideologies of power justify themselves in exactly this way, they justify the destruction of whatever would stand in the way of progress and the liberation of humanity. We suffer on account of God’s patience. And yet, we need his patience. God, who became a lamb, tells us that the world is saved by the Crucified One, not by those who crucified him. The world is redeemed by the patience of God. It is destroyed by the impatience of man.

One of the basic characteristics of a shepherd must be to love the people entrusted to him, even as he loves Christ whom he serves. “Feed my sheep”, says Christ to Peter, and now, at this moment, he says it to me as well. Feeding means loving, and loving also means being ready to suffer. Loving means giving the sheep what is truly good, the nourishment of God’s truth, of God’s word, the nourishment of his presence, which he gives us in the Blessed Sacrament. My dear friends – at this moment I can only say: pray for me, that I may learn to love the Lord more and more. Pray for me, that I may learn to love his flock more and more – in other words, you, the holy Church, each one of you and all of you together. Pray for me, that I may not flee for fear of the wolves. Let us pray for one another, that the Lord will carry us and that we will learn to carry one another.

The second symbol used in today’s liturgy to express the inauguration of the Petrine Ministry is the presentation of the fisherman’s ring. Peter’s call to be a shepherd, which we heard in the Gospel, comes after the account of a miraculous catch of fish: after a night in which the disciples had let down their nets without success, they see the Risen Lord on the shore. He tells them to let down their nets once more, and the nets become so full that they can hardly pull them in; 153 large fish: “and although there were so many, the net was not torn” (Jn 21:11). This account, coming at the end of Jesus’s earthly journey with his disciples, corresponds to an account found at the beginning: there too, the disciples had caught nothing the entire night; there too, Jesus had invited Simon once more to put out into the deep. And Simon, who was not yet called Peter, gave the wonderful reply: “Master, at your word I will let down the nets.” And then came the conferral of his mission: “Do not be afraid. Henceforth you will be catching men” (Lk 5:1-11). Today too the Church and the successors of the Apostles are told to put out into the deep sea of history and to let down the nets, so as to win men and women over to the Gospel – to God, to Christ, to true life. The Fathers made a very significant commentary on this singular task. This is what they say: for a fish, created for water, it is fatal to be taken out of the sea, to be removed from its vital element to serve as human food. But in the mission of a fisher of men, the reverse is true. We are living in alienation, in the salt waters of suffering and death; in a sea of darkness without light. The net of the Gospel pulls us out of the waters of death and brings us into the splendour of God’s light, into true life. It is really true: as we follow Christ in this mission to be fishers of men, we must bring men and women out of the sea that is salted with so many forms of alienation and onto the land of life, into the light of God. It is really so: the purpose of our lives is to reveal God to men. And only where God is seen does life truly begin. Only when we meet the living God in Christ do we know what life is. We are not some casual and meaningless product of evolution. Each of us is the result of a thought of God. Each of us is willed, each of us is loved, each of us is necessary. There is nothing more beautiful than to be surprised by the Gospel, by the encounter with Christ. There is nothing more beautiful than to know Him and to speak to others of our friendship with Him. The task of the shepherd, the task of the fisher of men, can often seem wearisome. But it is beautiful and wonderful, because it is truly a service to joy, to God’s joy which longs to break into the world.

Here I want to add something: both the image of the shepherd and that of the fisherman issue an explicit call to unity. “I have other sheep that are not of this fold; I must lead them too, and they will heed my voice. So there shall be one flock, one shepherd” (Jn 10:16); these are the words of Jesus at the end of his discourse on the Good Shepherd. And the account of the 153 large fish ends with the joyful statement: “although there were so many, the net was not torn” (Jn 21:11). Alas, beloved Lord, with sorrow we must now acknowledge that it has been torn! But no – we must not be sad! Let us rejoice because of your promise, which does not disappoint, and let us do all we can to pursue the path towards the unity you have promised. Let us remember it in our prayer to the Lord, as we plead with him: yes, Lord, remember your promise. Grant that we may be one flock and one shepherd! Do not allow your net to be torn, help us to be servants of unity!

At this point, my mind goes back to 22 October 1978, when Pope John Paul II began his ministry here in Saint Peter’s Square. His words on that occasion constantly echo in my ears: “Do not be afraid! Open wide the doors for Christ!” The Pope was addressing the mighty, the powerful of this world, who feared that Christ might take away something of their power if they were to let him in, if they were to allow the faith to be free. Yes, he would certainly have taken something away from them: the dominion of corruption, the manipulation of law and the freedom to do as they pleased. But he would not have taken away anything that pertains to human freedom or dignity, or to the building of a just society. The Pope was also speaking to everyone, especially the young. Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way? If we let Christ enter fully into our lives, if we open ourselves totally to him, are we not afraid that He might take something away from us? Are we not perhaps afraid to give up something significant, something unique, something that makes life so beautiful? Do we not then risk ending up diminished and deprived of our freedom? And once again the Pope said: No! If we let Christ into our lives, we lose nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful and great. No! Only in this friendship are the doors of life opened wide. Only in this friendship is the great potential of human existence truly revealed. Only in this friendship do we experience beauty and liberation. And so, today, with great strength and great conviction, on the basis of long personal experience of life, I say to you, dear young people: Do not be afraid of Christ! He takes nothing away, and he gives you everything. When we give ourselves to him, we receive a hundredfold in return. Yes, open, open wide the doors to Christ – and you will find true life. Amen.

Let us pray for Pope Benedict XVI, thanking God for giving us such a wonderful shepherd to guide His Church, feed His lambs and tend His sheep!

Jesus and St. Peter

Among the rituals of the Papal Paschal celebrations is a brief, but poignant custom of the Holy Father venerating an icon of the Risen Christ. This simple custom calls to mind the tradition that Christ appeared first to the Prince of the Apostles and then to the remaining ten. This ritual dates back to the 14th century and was restored to the Easter Sunday liturgy by the Venerable Pope John Paul II during the 2000 Jubilee Year.

St. Paul tells us in one of his Epistles that Christ first appeared to Cephas (Peter) and then to the rest of the Apostles. In today's Gospel, taken from St. John's account, Mary Magdalene runs to tell the Apostles. Peter and John hurry towards the tomb; however, because he is younger, the beloved disciple arrives first. Peter, huffing along, gets there shortly thereafter. However, even though John reaches the tomb first, he does not enter it. He defers to Peter. As soon as Peter arrives, he enters the tomb and inspects it; but, he cannot yet make sense of what has happened. John then enters the tomb, sees the burial cloths and the head wrapping and seems to understand.

St. John gives us an interesting perspective on Peter's supremacy. The beloved disciple gets to the tomb ahead of Peter, but, he chooses not to enter. He waits for Peter. He respects Peter's authority because such was conferred by no less than Jesus, Himself. It falls to Peter to enter the empty tomb, inspect it and see for himself. He is the first of the surviving Apostles, then, to see the effects of the resurrection. He is also the first, at Pentecost, to boldly proclaim to the crowds that Jesus is risen.

The Holy Father is the Successor of St. Peter. He acts in and with the aouthority of Jesus, as His Vicar on Earth. He is called, first and foremost, to continuosly proclaim the message that Jesus has vanquished death, that He is victorious over sin. Peter's words resonate through all times in the message proclaimed by his successors.

This simple ritual of the Successor of St. Peter being the first to gaze upon the figure of the Risen Christ is not a mere sentimental gesture. It is a renewal of the Petrine ministry to preach the Risen Lord.

Urbi et Orbi

When God created the earth, the first utterance from his mouth was "Let there be light"! Thus, the light shone forth upon the earth. Creation begins with light. Centuries later, God once more utters, "Let there be light"! It is the eighth day, the dawn of the recreation of the Earth. The light that shines forth is from the abysmal tomb that held Christ Jesus. That light, is the Resurrection. Jesus bursts forth from the empty tomb, shedding the light of salvation and divine mercy throughout all of the world, throughout all times and to all peoples.

It is this theme of light that permeates throughout the Holy Father's Easter Urbi et Orbi message for 2011:

“In resurrectione tua, Christe, coeli et terra laetentur!In your resurrection, O Christ, let heaven and earth rejoice!” (Liturgy of the Hours).The Sun of Justice has burst forth from the darkeness of the tomb. Let us rejoice and be glad!

Dear Brothers and Sisters in Rome and across the world,

Easter morning brings us news that is ancient yet ever new: Christ is risen! The echo of this event, which issued forth from Jerusalem twenty centuries ago, continues to resound in the Church, deep in whose heart lives the vibrant faith of Mary, Mother of Jesus, the faith of Mary Magdalene and the other women who first discovered the empty tomb, and the faith of Peter and the other Apostles.

Right down to our own time – even in these days of advanced communications technology – the faith of Christians is based on that same news, on the testimony of those sisters and brothers who saw firstly the stone that had been rolled away from the empty tomb and then the mysterious messengers who testified that Jesus, the Crucified, was risen. And then Jesus himself, the Lord and Master, living and tangible, appeared to Mary Magdalene, to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, and finally to all eleven, gathered in the Upper Room (cf. Mk 16:9-14).

The resurrection of Christ is not the fruit of speculation or mystical experience: it is an event which, while it surpasses history, nevertheless happens at a precise moment in history and leaves an indelible mark upon it. The light which dazzled the guards keeping watch over Jesus’ tomb has traversed time and space. It is a different kind of light, a divine light, that has rent asunder the darkness of death and has brought to the world the splendour of God, the splendour of Truth and Goodness.

Just as the sun’s rays in springtime cause the buds on the branches of the trees to sprout and open up, so the radiance that streams forth from Christ’s resurrection gives strength and meaning to every human hope, to every expectation, wish and plan. Hence the entire cosmos is rejoicing today, caught up in the springtime of humanity, which gives voice to creation’s silent hymn of praise. The Easter Alleluia, resounding in the Church as she makes her pilgrim way through the world, expresses the silent exultation of the universe and above all the longing of every human soul that is sincerely open to God, giving thanks to him for his infinite goodness, beauty and truth.

“In your resurrection, O Christ, let heaven and earth rejoice.” To this summons to praise, which arises today from the heart of the Church, the “heavens” respond fully: the hosts of angels, saints and blessed souls join with one voice in our exultant song. In heaven all is peace and gladness. But alas, it is not so on earth! Here, in this world of ours, the Easter alleluia still contrasts with the cries and laments that arise from so many painful situations: deprivation, hunger, disease, war, violence. Yet it was for this that Christ died and rose again! He died on account of sin, including ours today, he rose for the redemption of history, including our own. So my message today is intended for everyone, and, as a prophetic proclamation, it is intended especially for peoples and communities who are undergoing a time of suffering, that the Risen Christ may open up for them the path of freedom, justice and peace.

May the Land which was the first to be flooded by the light of the Risen One rejoice. May the splendour of Christ reach the peoples of the Middle East, so that the light of peace and of human dignity may overcome the darkness of division, hate and violence. In the current conflict in Libya, may diplomacy and dialogue take the place of arms and may those who suffer as a result of the conflict be given access to humanitarian aid. In the countries of northern Africa and the Middle East, may all citizens, especially young people, work to promote the common good and to build a society where poverty is defeated and every political choice is inspired by respect for the human person. May help come from all sides to those fleeing conflict and to refugees from various African countries who have been obliged to leave all that is dear to them; may people of good will open their hearts to welcome them, so that the pressing needs of so many brothers and sisters will be met with a concerted response in a spirit of solidarity; and may our words of comfort and appreciation reach all those who make such generous efforts and offer an exemplary witness in this regard.

May peaceful coexistence be restored among the peoples of Ivory Coast, where there is an urgent need to tread the path of reconciliation and pardon, in order to heal the deep wounds caused by the recent violence. May Japan find consolation and hope as it faces the dramatic consequences of the recent earthquake, along with other countries that in recent months have been tested by natural disasters which have sown pain and anguish.

May heaven and earth rejoice at the witness of those who suffer opposition and even persecution for their faith in Jesus Christ. May the proclamation of his victorious resurrection deepen their courage and trust.

Dear brothers and sisters! The risen Christ is journeying ahead of us towards the new heavens and the new earth (cf. Rev 21:1), in which we shall all finally live as one family, as sons of the same Father. He is with us until the end of time. Let us walk behind him, in this wounded world, singing Alleluia. In our hearts there is joy and sorrow, on our faces there are smiles and tears. Such is our earthly reality. But Christ is risen, he is alive and he walks with us. For this reason we sing and we walk, faithfully carrying out our task in this world with our gaze fixed on heaven.

Happy Easter to all of you!

Victimae Paschali Sequence

Traditionally chanted prior to the singing of the Alleluia, the Easter Sequence. Let us enjoy this beautiful prayer as we contemplate the triumph of our Lord over the grave!

The Easter Proclamation

One of the most beautiful chants of the Church's repertoire of prayers is the Exultet, the great Easter Proclamation. The Exultant stands as the Church's pre-eminent prayer of Paschal joy.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

The fulfillment of "very good"

In tonight's first Old Testament reading, the Church recounts the story of the creation of the world. Four times, Genesis notes that after God sees what He has created, he calls it good. On the fifth day, after creating man and woman in His own image and likeness, God sees his handiwork and calls it "very good."

The serpent, through trickery and deception, introduced sin into the garden, inducing and seducing Adam and Eve with forbidden fruit. In effect, the first meal in Scripture is eaten and God is not even the guest of honor in His own garden. With the fall, man is banished from Eden and the beauty of creation is distorted.

But, as Pope Benedict XVI explains in his homily for the Easter Vigil, our salvation history finds its origins in the creation and its culmination in the recreation that occured on the eighth day, after God had rested in the garden tomb from the incredible task of redemption, when He rose again, victorious.

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

The liturgical celebration of the Easter Vigil makes use of two eloquent signs. First there is the fire that becomes light. As the procession makes its way through the church, shrouded in the darkness of the night, the light of the Paschal Candle becomes a wave of lights, and it speaks to us of Christ as the true morning star that never sets – the Risen Lord in whom light has conquered darkness. The second sign is water. On the one hand, it recalls the waters of the Red Sea, decline and death, the mystery of the Cross. But now it is presented to us as spring water, a life-giving element amid the dryness. Thus it becomes the image of the sacrament of baptism, through which we become sharers in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Yet these great signs of creation, light and water, are not the only constituent elements of the liturgy of the Easter Vigil. Another essential feature is the ample encounter with the words of sacred Scripture that it provides. Before the liturgical reform there were twelve Old Testament readings and two from the New Testament. The New Testament readings have been retained. The number of Old Testament readings has been fixed at seven, but depending upon the local situation, they may be reduced to three. The Church wishes to offer us a panoramic view of whole trajectory of salvation history, starting with creation, passing through the election and the liberation of Israel to the testimony of the prophets by which this entire history is directed ever more clearly towards Jesus Christ. In the liturgical tradition all these readings were called prophecies. Even when they are not directly foretelling future events, they have a prophetic character, they show us the inner foundation and orientation of history. They cause creation and history to become transparent to what is essential. In this way they take us by the hand and lead us towards Christ, they show us the true Light.

At the Easter Vigil, the journey along the paths of sacred Scripture begins with the account of creation. This is the liturgy’s way of telling us that the creation story is itself a prophecy. It is not information about the external processes by which the cosmos and man himself came into being. The Fathers of the Church were well aware of this. They did not interpret the story as an account of the process of the origins of things, but rather as a pointer towards the essential, towards the true beginning and end of our being. Now, one might ask: is it really important to speak also of creation during the Easter Vigil? Could we not begin with the events in which God calls man, forms a people for himself and creates his history with men upon the earth? The answer has to be: no. To omit the creation would be to misunderstand the very history of God with men, to diminish it, to lose sight of its true order of greatness. The sweep of history established by God reaches back to the origins, back to creation. Our profession of faith begins with the words: “We believe in God, the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth”. If we omit the beginning of the Credo, the whole history of salvation becomes too limited and too small. The Church is not some kind of association that concerns itself with man’s religious needs but is limited to that objective. No, she brings man into contact with God and thus with the source of all things. Therefore we relate to God as Creator, and so we have a responsibility for creation. Our responsibility extends as far as creation because it comes from the Creator. Only because God created everything can he give us life and direct our lives. Life in the Church’s faith involves more than a set of feelings and sentiments and perhaps moral obligations. It embraces man in his entirety, from his origins to his eternal destiny. Only because creation belongs to God can we place ourselves completely in his hands. And only because he is the Creator can he give us life for ever. Joy over creation, thanksgiving for creation and responsibility for it all belong together.

The central message of the creation account can be defined more precisely still. In the opening words of his Gospel, Saint John sums up the essential meaning of that account in this single statement: “In the beginning was the Word”. In effect, the creation account that we listened to earlier is characterized by the regularly recurring phrase: “And God said ...” The world is a product of the Word, of the Logos, as Saint John expresses it, using a key term from the Greek language. “Logos” means “reason”, “sense”, “word”. It is not reason pure and simple, but creative Reason, that speaks and communicates itself. It is Reason that both is and creates sense. The creation account tells us, then, that the world is a product of creative Reason. Hence it tells us that, far from there being an absence of reason and freedom at the origin of all things, the source of everything is creative Reason, love, and freedom. Here we are faced with the ultimate alternative that is at stake in the dispute between faith and unbelief: are irrationality, lack of freedom and pure chance the origin of everything, or are reason, freedom and love at the origin of being? Does the primacy belong to unreason or to reason? This is what everything hinges upon in the final analysis. As believers we answer, with the creation account and with John, that in the beginning is reason. In the beginning is freedom. Hence it is good to be a human person. It is not the case that in the expanding universe, at a late stage, in some tiny corner of the cosmos, there evolved randomly some species of living being capable of reasoning and of trying to find rationality within creation, or to bring rationality into it. If man were merely a random product of evolution in some place on the margins of the universe, then his life would make no sense or might even be a chance of nature. But no, Reason is there at the beginning: creative, divine Reason. And because it is Reason, it also created freedom; and because freedom can be abused, there also exist forces harmful to creation. Hence a thick black line, so to speak, has been drawn across the structure of the universe and across the nature of man. But despite this contradiction, creation itself remains good, life remains good, because at the beginning is good Reason, God’s creative love. Hence the world can be saved. Hence we can and must place ourselves on the side of reason, freedom and love – on the side of God who loves us so much that he suffered for us, that from his death there might emerge a new, definitive and healed life.

The Old Testament account of creation that we listened to clearly indicates this order of realities. But it leads us a further step forward. It has structured the process of creation within the framework of a week leading up to the Sabbath, in which it finds its completion. For Israel, the Sabbath was the day on which all could participate in God’s rest, in which man and animal, master and slave, great and small were united in God’s freedom. Thus the Sabbath was an expression of the Covenant between God and man and creation. In this way, communion between God and man does not appear as something extra, something added later to a world already fully created. The Covenant, communion between God and man, is inbuilt at the deepest level of creation. Yes, the Covenant is the inner ground of creation, just as creation is the external presupposition of the Covenant. God made the world so that there could be a space where he might communicate his love, and from which the response of love might come back to him. From God’s perspective, the heart of the man who responds to him is greater and more important than the whole immense material cosmos, for all that the latter allows us to glimpse something of God’s grandeur.

Easter and the paschal experience of Christians, however, now require us to take a further step. The Sabbath is the seventh day of the week. After six days in which man in some sense participates in God’s work of creation, the Sabbath is the day of rest. But something quite unprecedented happened in the nascent Church: the place of the Sabbath, the seventh day, was taken by the first day. As the day of the liturgical assembly, it is the day for encounter with God through Jesus Christ who as the Risen Lord encountered his followers on the first day, Sunday, after they had found the tomb empty. The structure of the week is overturned. No longer does it point towards the seventh day, as the time to participate in God’s rest. It sets out from the first day as the day of encounter with the Risen Lord. This encounter happens afresh at every celebration of the Eucharist, when the Lord enters anew into the midst of his disciples and gives himself to them, allows himself, so to speak, to be touched by them, sits down at table with them. This change is utterly extraordinary, considering that the Sabbath, the seventh day seen as the day of encounter with God, is so profoundly rooted in the Old Testament. If we also bear in mind how much the movement from work towards the rest-day corresponds to a natural rhythm, the dramatic nature of this change is even more striking. This revolutionary development that occurred at the very the beginning of the Church’s history can be explained only by the fact that something utterly new happened that day. The first day of the week was the third day after Jesus’ death. It was the day when he showed himself to his disciples as the Risen Lord. In truth, this encounter had something unsettling about it. The world had changed. This man who had died was now living with a life that was no longer threatened by any death. A new form of life had been inaugurated, a new dimension of creation. The first day, according to the Genesis account, is the day on which creation begins. Now it was the day of creation in a new way, it had become the day of the new creation. We celebrate the first day. And in so doing we celebrate God the Creator and his creation. Yes, we believe in God, the Creator of heaven and earth. And we celebrate the God who was made man, who suffered, died, was buried and rose again. We celebrate the definitive victory of the Creator and of his creation. We celebrate this day as the origin and the goal of our existence. We celebrate it because now, thanks to the risen Lord, it is definitively established that reason is stronger than unreason, truth stronger than lies, love stronger than death. We celebrate the first day because we know that the black line drawn across creation does not last for ever. We celebrate it because we know that those words from the end of the creation account have now been definitively fulfilled: “God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31). Amen.

On this holy night, let us pray that the Lord renew His Church and reinvigorate the hearts of His faithful, renewing the face of the Earth, as we prayed in the first psalm of the Vigil's liturgy.

And he descended into hell...

Today, the Church joins St. Mary Magdalene and the other holy women in silent vigil in front of the Lord's tomb. There is a beautiful tradition about the journey of Christ's soul during this time.

A fourth century Greek homily, whose author is unknown, records the event (account taken from the blog, "The Crossroads Initiative"):

Something strange is happening - there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh and hell trembles with fear.

He has gone to search for our first parent, as for a lost sheep. Greatly desiring to visit those who live in darkness and in the shadow of death, he has gone to free from sorrow the captives Adam and Eve, he who is both God and the son of Eve. The Lord approached them bearing the cross, the weapon that had won him the victory. At the sight of him Adam, the first man he had created, struck his breast in terror and cried out to everyone: “My Lord be with you all”. Christ answered him: “And with your spirit”. He took him by the hand and raised him up, saying: “Awake, O sleeper, and rise from the dead, and Christ will give you light”.

I am your God, who for your sake have become your son. Out of love for you and for your descendants I now by my own authority command all who are held in bondage to come forth, all who are in darkness to be enlightened, all who are sleeping to arise. I order you, O sleeper, to awake. I did not create you to be held a prisoner in hell. Rise from the dead, for I am the life of the dead. Rise up, work of my hands, you who were created in my image. Rise, let us leave this place, for you are in me and I am in you; together we form only one person and we cannot be separated. For your sake I, your God, became your son; I, the Lord, took the form of a slave; I, whose home is above the heavens, descended to the earth and beneath the earth. For your sake, for the sake of man, I became like a man without help, free among the dead. For the sake of you, who left a garden, I was betrayed to the Jews in a garden, and I was crucified in a garden.

See on my face the spittle I received in order to restore to you the life I once breathed into you. See there the marks of the blows I received in order to refashion your warped nature in my image. On my back see the marks of the scourging I endured to remove the burden of sin that weighs upon your back. See my hands, nailed firmly to a tree, for you who once wickedly stretched out your hand to a tree.

I slept on the cross and a sword pierced my side for you who slept in paradise and brought forth Eve from your side. My side has healed the pain in yours. My sleep will rouse you from your sleep in hell. The sword that pierced me has sheathed the sword that was turned against you.

Rise, let us leave this place. The enemy led you out of the earthly paradise. I will not restore you to that paradise, but I will enthrone you in heaven. I forbade you the tree that was only a symbol of life, but see, I who am life itself am now one with you. I appointed cherubim to guard you as slaves are guarded, but now I make them worship you as God. The throne formed by cherubim awaits you, its bearers swift and eager. The bridal chamber is adorned, the banquet is ready, the eternal dwelling places are prepared, the treasure houses of all good things lie open. The kingdom of heaven has been prepared for you from all eternity.

Perhaps the best depiction of this beautiful episode is the painting by Fra Angelico. Painted in the mid 15th century, the piece is called "Christ in Limbo."

From the looks of it, one can make out the holy patriarch Abraham, Eve (who seems to be behind him), and even John the Baptist. The demons seem to be crouching in fear in the left corner as Christ extends his hands to the exiles in limbo. One demon appears flattened by the door that the Savior has just broken down.

In a few hours, my parish will begin its celebration of the Easter Vigil. For many of you who read this blog, the Paschal joy has already come to you. I will pray for all of you this evening and ask for your prayers in turn.

Friday, April 22, 2011

A Pilgrimage of Sorts

We don't have Stational Churches in my little corner of the South Texas hinterland. I suppose that not many areas have them. However, we have a unique custom down here involving Holy Thursday and visitations. After assisting at the Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper in their particular parhishes, many of the faithful embark on a pilgrimage where they visit six other parishes. All told, by the time the evening is over, they will have visited seven churches total (including their own parish).

Your intrepid blogger embarked on her own journey throughout the city. A friend of mine from the parish came along. Obviously, we started our journey at home base, our parish.

As I was praying, I could not help but rememince about how things had been 10 years ago. The rector decided that we should rent trolleys from the city's metro transit system and do our own tour of seven churches. People really enjoyed the tour. As we wound our way through the city streets we prayed the rosary and sang hymns. The excursion made me think of the Canterbury Tales. While we weren't spinning yarns like the Medieval pilgrims, we were sharing fellowship as we made our pilgrimage. It was prayerful and enjoyable.

Remaining in downtown, we went to my dad's parish for the next visitation. All throughout the trip, I played some Gregorian chant to get my friend and I in the pilgrimage mode.

Your intrepid blogger embarked on her own journey throughout the city. A friend of mine from the parish came along. Obviously, we started our journey at home base, our parish.

This picture was actually taken today. Last night, it looked beautiful; however, although the Tabernacle was bathed with the light of dozens of candles, it was still too dim to take a decent picture. We stayed in prayer for a bit and then proceeded on to the tour.

I did not get a chance to photograph the next two stops. It did not occur to me until the following stop that I should document this nocturnal pilgrimage. Here is the next photograph.

Talk about being bathed in candlelight. It was quite an impact to be greeted by what seemed to be a couple of hundred candles burning brightly. As I knelt down to pray before the Blessed Sacrament, the warmth of all of those candles hit my face. While we were at prayer, a steady stream of faithful came in to visit. We ran into some of the folks whom we had seen at the other parishes. All of us were making that same journey.

We made our way downtown to the Cathedral. I used to volunteer at the Cathedral, helping out with liturgy. We would use the back Blessed Sacrament chapel as the Altar of Repose, but, times have changed.

As I was praying, I could not help but rememince about how things had been 10 years ago. The rector decided that we should rent trolleys from the city's metro transit system and do our own tour of seven churches. People really enjoyed the tour. As we wound our way through the city streets we prayed the rosary and sang hymns. The excursion made me think of the Canterbury Tales. While we weren't spinning yarns like the Medieval pilgrims, we were sharing fellowship as we made our pilgrimage. It was prayerful and enjoyable.

Remaining in downtown, we went to my dad's parish for the next visitation. All throughout the trip, I played some Gregorian chant to get my friend and I in the pilgrimage mode.

I found it fascinating that both the Cathedral and my dad's parish decided to place the Altar of Repose in the area where the statues of the Blessed Mother are normally located. It is actually a most appropriate location because Mary, the true Ark of the Covenant, was the first Tabernacle. Just as the Ark of the Old Covenant held the manna from heaven, the tablets of the Mosaic law and the rod of Aaron, the first priest, Mary held in her womb the True Bread come down from heaven, the fulfillment of the Law and the True High Priest, Jesus Christ.

Our next stop was a tiny mission parish located just outside of our community college. This remote little church also houses a retreat center.

Once again, the lights of nearly 200 candles bathed the area of the Altar of Repose. I could still smell the sweet aroma of the incense that had been used for the Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper. At each stop, I prayed for two friends of mine, a local prelate and an Oratorian priest who works for the Holy See. I had promised them that I would pray for them throughout the night. Of course, I also prayed for the Holy Father, given the exhortation that he preached on how our prayers comfort him. This was there night, as the Sacrament of Holy Orders was also instituted at the Last Supper. Holy Orders and the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist are intrinscally united. They are inseparable. In order for the Church to "do this in memory of me", she needs priests to offer the Holy Sacrifice. Thus, throughout the evening, my two friends and the Holy Father were never far from my mind nor my heart.

The next stop was to a parish that is commonly known down here as the "blue church". The entire interior of the church is painted a bright blue.

We happened to come upon what seemed to be an all-night vigil sponsored by the Nocturnal Adoration Society. It was most edifying to see the faithful praying together and singing. The faithful seemed oblivious to the consistent traffic entering and departing the church.

My friend and I returned back to our parish so that we can spend additional time in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. She asked me why we visit seven churches. I told her that I really did not know the answer. We both compared it to the Roman stational churches. However, as I type this blog entry, I am wondering if there might be a deeper reasoning. After Jesus' arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane, the Gospel accounts tell us that he was taken to several different places. He went before Annas, Caiphas, Pilate and Herod and back to Pilate. St. Peter, despite his foibles and flaws, desperately wanted to be where Jesus was. He followed closely behind until his denials caught up to him and he left the scene. St. John was able to follow him all the way to Calvary.

And so it is with us. Despite our sins, our foibles and our weaknesses, we want to follow Jesus. Yes, we could have stayed in our parishes to pray there, but, there is something about making a pilgrimage, about making the symbolic journey to accompany Jesus that goes beyond the pious local custom. It is about wanting to follow Jesus and join the rest of our brothers and sisters in that journey.

The Reproaches

The Reproaches is the chant that is proper to the Veneration of the Cross. "My people, what have I done to you? How have I offended you? Answer me."

It is consummated

Today, the Church marks Good Friday. According to the Church's ancient tradition, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is not celebrated on this day. Instead, the Church commemorates the Passion of her Lord.

In the Memorial of the Roman Canon, we call to mind the various sacrifices made throughout the history of Ancient Israel. We recall the sacrifice of Abel and the "bread and wine offered by your priest Melchisedek". There is also another sacrifice that we recall, that of Abraham.

In Genesis, we note that God entered into a covenant with Abraham. Abraham cuts up several animals in two. The ancient practice of the covenant was that both parties would walk in between the split carcasses and pledge that if either of them breaks the covenant, their fate would be similar to the dead animals. God, knowing full well the frailty of human nature, causes Abraham to fall into a deep sleep. When Abraham regains consciousness, he sees a flaming brazier moving between the carcasses.

Later on, Abraham, who is already well past 100, faces perhaps the most important test of his faith. God asks him to sacrifice his beloved son, the child of the covenant, the heir who is supposed to make him the father of many nations. Abraham and Isaac make the trek up Mount Moriah. Isaac carries the wood up the mount. Such a heavy load would have been too much for the aged Abraham to bear. A prelate friend of mine notes that Rabbinic scholars believe that Isaac must have been a young man by this time. This may very well be the case, which makes the story all the more remarkable. At this point, Isaac has not married, let alone, sired any children. However, even though God asked Abraham to do the unthinkable and offer his beloved Isaac as a holocaust offering, Abraham had the faith to believe that God would restore this child of the promise back to him. Isaac, for his part, had to have faith, as well, since he submitted himself to whatever his father requested.

As Abraham prepares to sacrifice Isaac, God sends an angel to stop the patriarch. He sees Abraham's faith and credits it to him as an act of righteousness. Isaac is spared. In his place, father and son offer a ram which they saw caught in the thickets.

Generations later, we see the fulfillment of Abraham's sacrifice. The Old Testament foreshadows what will be fulfilled in the New Testament. In this case, the eternal Beloved Son of the Father is the one who is offered as the supreme sacrifice of the new and everlasting covenant. The Father asks his son, Jesus, to lay down His life in holocaust. Out of His immense love for the Father, Jesus willingly accepts death on a cross. Like Isaac, who prefigured Him, Jesus carries the wood, this time, that of the Cross, up Mount Calvary. The fire that was meant to consume Isaac becomes, in Christ, the fire of divine love, an intense love that compels Him to perfectly fulfill the Father's will.

But, there is another element here. If Abraham had complete trust in God, how much more did the Blessed Mother trust in the Lord, especially at the moment when all seemed lost. She united herself to her Son's saving ministry when she gave the Archangel Gabriel her fiat to become the Mother of God. "I am the handmaid of the Lord" she said. "Be it done unto me according to your will." This acceptance was not merely about agreeing to bear the Christ child. It was a commitment to be with Jesus through the end. Mary held on, staying with her Son, walking alongside of Him as he carried that wood up the mount. Like Abraham, Mary did not withhold her Son, the true Child of the promise, from God. Through her prayers, she united herself to Jesus, believing that whatever God promised would be fulfilled.

When Jesus says, "It is consummated", I believe that he does not just speak about his ministry. What he has consummated is the fulfillment of all of the sacrifices of Ancient Israel, from Abel, to Melchisedek, to Abraham, to Moses and to David. What he has consummated is the act of undoing the damage caused when Adam and Eve said "No". Jesus' perfect obedience, prefigured by the obedience of Isaac, brings forth salvation.

Isaac prefigured the sacrifice. Isaiah foretold the suffering of the servant. Jesus consummated all of this, perfectly fulfilling what had been foretold.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

"I have greatly desired to eat this supper with you..."

A prelate friend of mine often tells us in his homilies that God years to be yearned for. Jesus tells the Apostolic band that he has greatly desired to eat the Passover meal with them. This is a profound statement because He knew that within hours, all would flee and abandon Him, one would deny Him and the last one would betray Him. Yet, Jesus still yearned for their company.

In the Papal Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper, Pope Benedict XVI expounds on this theme in his eloquent homily.

Dear Brothers and Sisters!

“I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer” (Lk 22:15). With these words Jesus began the celebration of his final meal and the institution of the Holy Eucharist. Jesus approached that hour with eager desire. In his heart he awaited the moment when he would give himself to his own under the appearance of bread and wine. He awaited that moment which would in some sense be the true messianic wedding feast: when he would transform the gifts of this world and become one with his own, so as to transform them and thus inaugurate the transformation of the world. In this eager desire of Jesus we can recognize the desire of God himself – his expectant love for mankind, for his creation. A love which awaits the moment of union, a love which wants to draw mankind to itself and thereby fulfil the desire of all creation, for creation eagerly awaits the revelation of the children of God (cf. Rom 8:19). Jesus desires us, he awaits us. But what about ourselves? Do we really desire him? Are we anxious to meet him? Do we desire to encounter him, to become one with him, to receive the gifts he offers us in the Holy Eucharist? Or are we indifferent, distracted, busy about other things? From Jesus’ banquet parables we realize that he knows all about empty places at table, invitations refused, lack of interest in him and his closeness. For us, the empty places at the table of the Lord’s wedding feast, whether excusable or not, are no longer a parable but a reality, in those very countries to which he had revealed his closeness in a special way. Jesus also knew about guests who come to the banquet without being robed in the wedding garment – they come not to rejoice in his presence but merely out of habit, since their hearts are elsewhere. In one of his homilies Saint Gregory the Great asks: Who are these people who enter without the wedding garment? What is this garment and how does one acquire it? He replies that those who are invited and enter do in some way have faith. It is faith which opens the door to them. But they lack the wedding garment of love. Those who do not live their faith as love are not ready for the banquet and are cast out. Eucharistic communion requires faith, but faith requires love; otherwise, even as faith, it is dead.

From all four Gospels we know that Jesus’ final meal before his passion was also a teaching moment. Once again, Jesus urgently set forth the heart of his message. Word and sacrament, message and gift are inseparably linked. Yet at his final meal, more than anything else, Jesus prayed. Matthew, Mark and Luke use two words in describing Jesus’ prayer at the culmination of the meal: “eucharístesas” and “eulógesas” – the verbs “to give thanks” and “to bless”. The upward movement of thanking and the downward movement of blessing go together. The words of transubstantiation are part of this prayer of Jesus. They are themselves words of prayer. Jesus turns his suffering into prayer, into an offering to the Father for the sake of mankind. This transformation of his suffering into love has the power to transform the gifts in which he now gives himself. He gives those gifts to us, so that we, and our world, may be transformed. The ultimate purpose of Eucharistic transformation is our own transformation in communion with Christ. The Eucharist is directed to the new man, the new world, which can only come about from God, through the ministry of God’s Servant.

From Luke, and especially from John, we know that Jesus, during the Last Supper, also prayed to the Father – prayers which also contain a plea to his disciples of that time and of all times. Here I would simply like to take one of these which, as John tells us, Jesus repeated four times in his Priestly Prayer. How deeply it must have concerned him! It remains his constant prayer to the Father on our behalf: the prayer for unity. Jesus explicitly states that this prayer is not meant simply for the disciples then present, but for all who would believe in him (cf. Jn 17:20). He prays that all may be one “as you, Father, are in me and I am in you, so that the world may believe” (Jn 17:21). Christian unity can exist only if Christians are deeply united to him, to Jesus. Faith and love for Jesus, faith in his being one with the Father and openness to becoming one with him, are essential. This unity, then, is not something purely interior or mystical. It must become visible, so visible as to prove before the world that Jesus was sent by the Father. Consequently, Jesus’ prayer has an underlying Eucharistic meaning which Paul clearly brings out in the First Letter to the Corinthians: “The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many, are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:16ff.). With the Eucharist, the Church is born. All of us eat the one bread and receive the one body of the Lord; this means that he opens each of us up to something above and beyond us. He makes all of us one. The Eucharist is the mystery of the profound closeness and communion of each individual with the Lord and, at the same time, of visible union between all. The Eucharist is the sacrament of unity. It reaches the very mystery of the Trinity and thus creates visible unity. Let me say it again: it is an extremely personal encounter with the Lord and yet never simply an act of individual piety. Of necessity, we celebrate it together. In each community the Lord is totally present. Yet in all the communities he is but one. Hence the words “una cum Papa nostro et cum episcopo nostro” are a requisite part of the Church’s Eucharistic Prayer. These words are not an addendum of sorts, but a necessary expression of what the Eucharist really is. Furthermore, we mention the Pope and the Bishop by name: unity is something utterly concrete, it has names. In this way unity becomes visible; it becomes a sign for the world and a concrete criterion for ourselves.

Saint Luke has preserved for us one concrete element of Jesus’ prayer for unity: “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you, that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren” (Lk 22:31). Today we are once more painfully aware that Satan has been permitted to sift the disciples before the whole world. And we know that Jesus prays for the faith of Peter and his successors. We know that Peter, who walks towards the Lord upon the stormy waters of history and is in danger of sinking, is sustained ever anew by the Lord’s hand and guided over the waves. But Jesus continues with a prediction and a mandate. “When you have turned again…”. Every human being, save Mary, has constant need of conversion. Jesus tells Peter beforehand of his coming betrayal and conversion. But what did Peter need to be converted from? When first called, terrified by the Lord’s divine power and his own weakness, Peter had said: “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” (Lk 5:8). In the light of the Lord, he recognizes his own inadequacy. Precisely in this way, in the humility of one who knows that he is a sinner, is he called. He must discover this humility ever anew. At Caesarea Philippi Peter could not accept that Jesus would have to suffer and be crucified: it did not fit his image of God and the Messiah. In the Upper Room he did not want Jesus to wash his feet: it did not fit his image of the dignity of the Master. In the Garden of Olives he wielded his sword. He wanted to show his courage. Yet before the servant girl he declared that he did not know Jesus. At the time he considered it a little lie which would let him stay close to Jesus. All his heroism collapsed in a shabby bid to be at the centre of things. We too, all of us, need to learn again to accept God and Jesus Christ as he is, and not the way we want him to be. We too find it hard to accept that he bound himself to the limitations of his Church and her ministers. We too do not want to accept that he is powerless in this world. We too find excuses when being his disciples starts becoming too costly, too dangerous. All of us need the conversion which enables us to accept Jesus in his reality as God and man. We need the humility of the disciple who follows the will of his Master. Tonight we want to ask Jesus to look to us, as with kindly eyes he looked to Peter when the time was right, and to convert us.

After Peter was converted, he was called to strengthen his brethren. It is not irrelevant that this task was entrusted to him in the Upper Room. The ministry of unity has its visible place in the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. Dear friends, it is a great consolation for the Pope to know that at each Eucharistic celebration everyone prays for him, and that our prayer is joined to the Lord’s prayer for Peter. Only by the prayer of the Lord and of the Church can the Pope fulfil his task of strengthening his brethren – of feeding the flock of Christ and of becoming the guarantor of that unity which becomes a visible witness to the mission which Jesus received from the Father.

“I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you”. Lord, you desire us, you desire me. You eagerly desire to share yourself with us in the Holy Eucharist, to be one with us. Lord, awaken in us the desire for you. Strengthen us in unity with you and with one another. Grant unity to your Church, so that the world may believe. Amen.

Tonight, Jesus yearns for our company, for our love. Like the Apostles, we, too, flee from Him, deny Him and betray Him because of our sins. Yet, Jesus eagerly desires our company. He years for us to yearn for Him.

This Triduum, let us make time to be with our Lord and to walk with Him.

The meaning of annointing

I meant to get up at the very early hour of 2:30AM Texas time to watch the live broadcast of the Papal Chrism Mass from St. Peter's Basilica. I managed to wake up for the chanting of the Gospel and then linger for the first few minutes of the homily and then, I fell asleep. When I woke up, it was time for Holy Communion. The spirit was certainly willing, but, the flesh was not up to par.

Nonetheless, for those of you who missed it, here is the text of the Holy Father's homily for the Chrism Mass as it appears on the Vatican Radio website:

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

At the heart of this morning's liturgy is the blessing of the holy oils - the oil for anointing catechumens, the oil for anointing the sick, and the chrism for the great sacraments that confer the Holy Spirit: confirmation, priestly ordination, episcopal ordination. In the sacraments the Lord touches us through the elements of creation. The unity between creation and redemption is made visible. The sacraments are an expression of the physicality of our faith, which embraces the whole person, body and soul. Bread and wine are fruits of the earth and work of human hands. The Lord chose them to be bearers of his presence. Oil is the symbol of the Holy Spirit and at the same time it points us towards Christ: the word "Christ" (Messiah) means "the anointed one". The humanity of Jesus, by virtue of the Son's union with the Father, is brought into communion with the Holy Spirit and is thus "anointed" in a unique way, penetrated by the Holy Spirit. What happened symbolically to the kings and priests of the Old Testament when they were instituted into their ministry by the anointing with oil, takes place in Jesus in all its reality: his humanity is penetrated by the power of the Holy Spirit. He opens our humanity for the gift of the Holy Spirit. The more we are united to Christ, the more we are filled with his Spirit, with the Holy Spirit. We are called "Christians": "anointed ones" - people who belong to Christ and hence have a share in his anointing, being touched by his Spirit. I wish not merely to be called Christian, but also to be Christian, said Saint Ignatius of Antioch. Let us allow these holy oils, which are consecrated at this time, to remind us of the task that is implicit in the word "Christian", let us pray that, increasingly, we may not only be called Christian but may actually be such.

In today's liturgy, three oils are blessed, as I mentioned earlier. They express three essential dimensions of the Christian life on which we may now reflect. First, there is the oil of catechumens. This oil indicates a first way of being touched by Christ and by his Spirit - an inner touch, by which the Lord draws people close to himself. Through this first anointing, which takes place even prior to baptism, our gaze is turned towards people who are journeying towards Christ - people who are searching for faith, searching for God. The oil of catechumens tells us that it is not only we who seek God: God himself is searching for us. The fact that he himself was made man and came down into the depths of human existence, even into the darkness of death, shows us how much God loves his creature, man. Driven by love, God has set out towards us. "Seeking me, you sat down weary ... let such labour not be in vain!", we pray in the Dies Irae. God is searching for me. Do I want to recognize him? Do I want to be known by him, found by him? God loves us. He comes to meet the unrest of our hearts, the unrest of our questioning and seeking, with the unrest of his own heart, which leads him to accomplish the ultimate for us. That restlessness for God, that journeying towards him, so as to know and love him better, must not be extinguished in us. In this sense we should always remain catechumens. "Constantly seek his face", says one of the Psalms (105:4). Saint Augustine comments as follows: God is so great as to surpass infinitely all our knowing and all our being. Knowledge of God is never exhausted. For all eternity, with ever increasing joy, we can always continue to seek him, so as to know him and love him more and more. "Our heart is restless until it rests in you", said Saint Augustine at the beginning of his Confessions. Yes, man is restless, because whatever is finite is too little. But are we truly restless for him? Have we perhaps become resigned to his absence, do we not seek to be self-sufficient? Let us not allow our humanity to be diminished in this way! Let us remain constantly on a journey towards him, longing for him, always open to receive new knowledge and love!

Then there is the oil for anointing the sick. Arrayed before us is a host of suffering people: those who hunger and thirst, victims of violence in every continent, the sick with all their sufferings, their hopes and their moments without hope, the persecuted, the downtrodden, the broken-hearted. Regarding the first mission on which Jesus sent the disciples, Saint Luke tells us: "he sent them out to preach the kingdom of God and to heal" (9:2). Healing is one of the fundamental tasks entrusted by Jesus to the Church, following the example that he gave as he travelled throughout the land healing the sick. To be sure, the Church's principal task is to proclaim the Kingdom of God. But this very proclamation must be a process of healing: "bind up the broken-hearted", we heard in today's first reading from the prophet Isaiah (61:1). The proclamation of God's Kingdom, of God's unlimited goodness, must first of all bring healing to broken hearts. By nature, man is a being in relation. But if the fundamental relationship, the relationship with God, is disturbed, then all the rest is disturbed as well. If our relationship with God is disturbed, if the fundamental orientation of our being is awry, we cannot truly be healed in body and soul. For this reason, the first and fundamental healing takes place in our encounter with Christ who reconciles us to God and mends our broken hearts. But over and above this central task, the Church's essential mission also includes the specific healing of sickness and suffering. The oil for anointing the sick is the visible sacramental expression of this mission. Since apostolic times, the healing vocation has matured in the Church, and so too has loving solicitude for those who are distressed in body and soul. This is also the occasion to say thank you to those sisters and brothers throughout the world who bring healing and love to the sick, irrespective of their status or religious affiliation. From Elizabeth of Hungary, Vincent de Paul, Louise de Marillac, Camillus of Lellis to Mother Teresa - to recall but a few names - we see, lighting up the world, a radiant procession of helpers streaming forth from God's love for the suffering and the sick. For this we thank the Lord at this moment. For this we thank all those who, by virtue of their faith and love, place themselves alongside the suffering, thereby bearing definitive witness to the goodness of God himself. The oil for anointing the sick is a sign of this oil of the goodness of heart that these people bring - together with their professional competence - to the suffering. Even without speaking of Christ, they make him manifest.

In third place, finally, is the most noble of the ecclesial oils, the chrism, a mixture of olive oil and aromatic vegetable oils. It is the oil used for anointing priests and kings, in continuity with the great Old Testament traditions of anointing. In the Church this oil serves chiefly for the anointing of confirmation and ordination. Today's liturgy links this oil with the promise of the prophet Isaiah: "You shall be called the priests of the Lord, men shall speak of you as the ministers of our God" (61:6). The prophet makes reference here to the momentous words of commission and promise that God had addressed to Israel on Sinai: "You shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation" (Ex 19:6). In and for the vast world, which was largely ignorant of God, Israel had to be as it were a shrine of God for all peoples, exercising a priestly function vis-à-vis the world. It had to bring the world to God, to open it up to him. In his great baptismal catechesis, Saint Peter applied this privilege and this commission of Israel to the entire community of the baptized, proclaiming: "But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God's own people, that you may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. Once you were no people but now you are God's people" (1 Pet 2:9f.) Baptism and confirmation are an initiation into this people of God that spans the world; the anointing that takes place in baptism and confirmation is an anointing that confers this priestly ministry towards mankind. Christians are a priestly people for the world. Christians should make the living God visible to the world, they should bear witness to him and lead people towards him. When we speak of this task in which we share by virtue of our baptism, it is no reason to boast. It poses a question to us that makes us both joyful and anxious: are we truly God's shrine in and for the world? Do we open up the pathway to God for others or do we rather conceal it? Have not we - the people of God - become to a large extent a people of unbelief and distance from God? Is it perhaps the case that the West, the heartlands of Christianity, are tired of their faith, bored by their history and culture, and no longer wish to know faith in Jesus Christ? We have reason to cry out at this time to God: "Do not allow us to become a 'non-people'! Make us recognize you again! Truly, you have anointed us with your love, you have poured out your Holy Spirit upon us. Grant that the power of your Spirit may become newly effective in us, so that we may bear joyful witness to your message!

For all the shame we feel over our failings, we must not forget that today too there are radiant examples of faith, people who give hope to the world through their faith and love. When Pope John Paul II is beatified on 1 May, we shall think of him, with hearts full of thankfulness, as a great witness to God and to Jesus Christ in our day, as a man filled with the Holy Spirit. Alongside him, we think of the many people he beatified and canonized, who give us the certainty that even today God's promise and commission do not fall on deaf ears.

I turn finally to you, dear brothers in the priestly ministry. Holy Thursday is in a special way our day. At the hour of the last Supper, the Lord instituted the new Testament priesthood. "Sanctify them in the truth" (Jn 17:17), he prayed to the Father, for the Apostles and for priests of all times. With great gratitude for the vocation and with humility for all our shortcomings, we renew at this hour our "yes" to the Lord's call: yes, I want to be intimately united to the Lord Jesus, in self-denial, driven on by the love of Christ. Amen.

In Ancient Greece, athletes used oil as a means of conditioning. Oil was also used for medicinal purposes, as related in the parable of the Good Samartian when the Samaritan used wine and oil on the victim's wounds.

As the Holy Father noted in his homily, in the Old Testament, oil was also used to annoint priests. It is interesting that Jesus, the true High Priest, was only annointed just days before entering into His Passion. It seems to me that this annointing, done in the house of Lazarus, ritually prepared Jesus for the supreme sacrifice that he was to offer on the Cross.

On this day, dedicated to our priests, let us pray for them and thank God for the gift He has bestowed on us through the Sacrament of Holy Orders.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)